Hello Queseanians,

The issue of maritime biodiversity has been gaining renewed attention recently, and I wanted to share some of the latest developments from the 3rd UN Ocean Summit, held in June 2025 in Nice. Below is some background information and context for the ongoing discussions aimed at protecting and sustainably managing our oceans.

What’s happening to maritime biodiversity?

The oceans around the world are facing serious challenges. Biodiversity is shrinking, and many marine ecosystems are under threat. Climate change is a big part of the problem, but human activities like shipping, overfishing, plastic pollution, and deep-sea mining are also taking a heavy toll. Because of this, it’s clear that we need a stronger, more unified way to manage and protect the oceans. Right now, the rules and regulations are scattered and don’t fully cover the areas beyond any country’s control. That’s where the “High Seas Treaty” comes in—it’s designed to close those gaps by bringing together different organizations and agreements to work more closely and effectively.

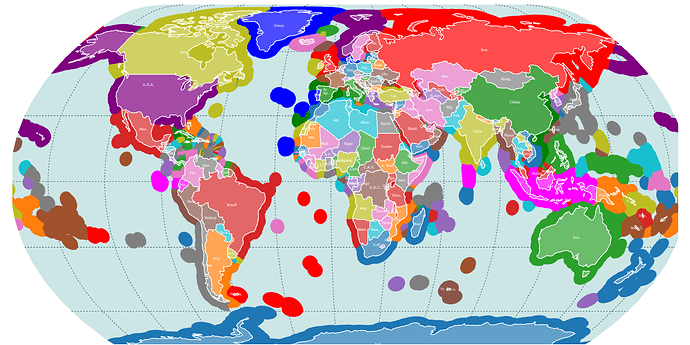

When we talk about areas beyond national jurisdiction, we mean the “high seas,” which are the parts of the ocean outside any country’s borders, and the international seabed, which lies beneath those waters (i.e. outside exclusive economic zones). Together, these areas make up about two-thirds of the world’s oceans.

What is the High Seas Treaty or the Global Ocean Treaty?

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea was adopted in 1982 and came into effect in 1994. It establishes a legal framework for activities in the world’s oceans, including rules regarding the allocation of States’ rights and jurisdiction in maritime areas, the use of the oceans, and the management of marine resources. The Convention also serves as a basis for further development of maritime regulations, including through the work of relevant international organizations such as the International Maritime Organization (IMO).

The regime set out in the Convention has been extended by additional instruments, addressing the priorities of States and supplementing the regulatory framework with the Agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) concerning the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement).

In 2015, the United Nations General Assembly resolved to develop an international, legally binding instrument under UNCLOS focused on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (UNGA resolution 69/292).

The 3rd UN ocean summit was held in June 2025 in Nice, France. At the conference, 19 more countries ratified the treaty, moving it closer to meeting the required threshold for implementation. As of the date of this article, 53 Parties have ratified the Agreement, which will enter into force 120 days after the 60th instrument of ratification is deposited.

The BBNJ Treaty will be an international legally binding treaty that will enter into force 120 days after the 60th ratification, acceptance, approval or accession. Its requirements will become effective once the BBNJ Treaty enters into force for the Parties.

What’s the Content of the Treaty

The BBNJ Agreement establishes an extensive framework dedicated to the conservation and sustainable utilisation of biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction across several key domains:

- Marine Genetic Resources (MGR), with provisions for the fair and equitable distribution of related benefits (Part II);

- Implementation of Area-Based Management Tools (ABMT), including the designation of marine protected areas (MPAs) (Part III);

- Procedures for conducting Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) (Part IV); and

- Initiatives for capacity-building and the transfer of marine technology (CB&TMT) (Part V).

Here you can download the exact text of the BBNJ Agreement :

Text of the BBNJ Agreement in English.pdf (329.8 KB)

The IMO has affirmed its commitment to actively participate in the implementation of the BBNJ Agreement, while ensuring that the new instrument does not adversely affect IMO’s current mandate or framework.

What will be the potential effects on the shipping industry and ocean-going cargo vessels?

A key element of the BBNJ Agreement is the introduction of more robust requirements for environmental impact assessments for activities that could affect marine biodiversity in the high seas.

The BBNJ Agreement will strengthen current anti-pollution measures from UNCLOS and the IMO, likely resulting in tighter enforcement of pollution controls, ballast water management, and waste disposal rules for ships near protected areas.

Given the IMO’s central role in implementing the BBNJ Agreement, it will likely take actions to support its provisions. Collaboration between the BBNJ framework and the IMO can help align new biodiversity measures with shipping regulations and minimize industry confusion.

What is my perspective on the effects of marine biological diversity on shipping?

For the shipping sector, this may result in additional reporting and compliance obligations, especially for operations located in or close to marine protected areas (MPAs). The Agreement also allows for the establishment of new protected zones in international waters. Potential effects on shipping include:

- New routing measures: Ships could be required to avoid certain sensitive areas, which may lead to adjustments in current shipping lanes.

- Operational restrictions: Regulations may limit discharges, noise, or other activities within or around MPAs to reduce environmental impact.

Looking ahead, my best guess would be that most likely shipping companies might be expected to include biodiversity protection measures in a plan, actively monitor its implementation, and continuously pursue improvements to minimize their impact on marine life.

Innovations and Industry Actions

In the U.S., approximately 80 endangered and threatened whales are struck by vessels each year off the West Coast, and more than a third of all North Atlantic right whale deaths in the Eastern U.S. are attributed to ship collisions. These collisions often cause severe injuries or death, posing a significant threat to already vulnerable whale populations.

To address this, ship-mounted camera systems have been developed that provide real-time detection of whales, increasing response time and potentially reducing vessel strikes. When used alone or alongside acoustic monitoring, this technology offers a promising way to significantly lower the risk of collisions.

For example, Hawaii-based shipping company Matson Navigation has begun equipping its vessels with thermal imaging cameras as part of a project in collaboration with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Cameras have already been installed on three of Matson’s ships to help prevent whale strikes.

These actions represent an important step toward the responsibility in safeguarding endangered marine species. Overall combining innovative detection technologies with industry commitment could play a crucial role in reducing whale mortality caused by vessel strikes and promoting coexistence between shipping and marine biodiversity.

In summary

In essence, the BBNJ Agreement will not fundamentally alter the freedom of navigation for ocean-going cargo ships, but it will likely introduce new environmental obligations, especially in relation to marine protected areas and environmental impact assessments.

It is a matter of time to explore its impact in international shipping.